Operational history

The first Zeros (pre-series A6M2) went into operation in July 1940. On 13 September 1940, the Zeros scored their first air-to-air victories when 13 A6M2s led by Lieutenant Saburo Shindo attacked 27 Soviet-built Polikarpov I-15s and I-16s of the Chinese Nationalist Air Force, shooting down all the fighters without loss to themselves. By the time they were redeployed a year later, the Zeros had shot down 99 Chinese aircraft

(266 according to other sources).

At the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor 420 Zeros were active in the Pacific. The carrier-borne Model 21 was the type encountered by the Americans. Its tremendous range of over 2,600 km (1,600 mi) allowed it to range farther from its carrier than expected, appearing over distant battlefronts and giving Allied commanders the impression that there were several times as many Zeros as actually existed.

The Zero quickly gained a fearsome reputation. Thanks to a combination of excellent maneuverability and firepower, it easily disposed of the motley collection of Allied aircraft sent against it in the Pacific in 1941. It proved a difficult opponent even for the Supermarine Spitfire. Although not as fast as the British fighter, the Mitsubishi fighter could out-turn the Spitfire with ease, could sustain a climb at a very steep angle, and could stay in the air for three times as long.

Soon, however, Allied pilots developed tactics to cope with the Zero. Due to its extreme agility, engaging a Zero in a traditional, turning dogfight was likely to be fatal. It was better to roar down from above in a high-speed pass, fire a quick burst, then climb quickly back up to altitude. (A short burst of fire from heavy machine guns or cannon was often enough to bring down the fragile Zero.) Such "boom-and-zoom" tactics were used successfully in the China Burma India Theater (CBI) by the "Flying Tigers" of the American Volunteer Group (AVG) against similarly maneuverable Japanese Army aircraft such as the Nakajima Ki-27 Nate and Ki-43 Oscar. AVG pilots were trained under their commander Claire Chennault's instructions to exploit the advantages of their P-40s, which were very sturdy, heavily armed, generally faster in a dive and level flight at low altitude, with a good rate of roll.

Another important maneuver was Lieutenant Commander John S. "Jimmy" Thach's "Thach Weave", in which two fighters would fly about 60 m

(200 ft) apart. If a Zero latched onto the tail of one of the fighters, the two aircraft would turn toward each other. If the Zero followed his original target through the turn, he would come into a position to be fired on by the target's wingman. This tactic was first used to good effect during the Battle of Midway, and later over the Solomon Islands. Many highly experienced Japanese aviators were lost in combat, resulting in a progressive decline in the quality of the opponents faced by Allied pilots, which became a significant factor in Allied successes. Unexpected heavy losses of these pilots at the battles of the Coral Sea and Midway dealt the Japanese carrier air force a blow from which it never fully recovered.

However, throughout the engagement at Midway, the Allied Pilots registered a high level of dissatisfaction with the current state of the Grumman F4F Wildcat. The Commanding Officer of the USS Yorktown noted:

The fighter pilots are very disappointed with the performance and length of sustained fire power of the F4F-4 airplanes. The Zero fighters could easily outmaneuver and out-climb the F4F-3, and the consensus of fighter pilot opinion is that the F4F-4 is even more sluggish and slow than the F4F-3. It is also felt that it was a mistake to put 6 guns on the F4F-4 and thus to reduce the rounds per gun. Many of our fighters ran out of ammunition even before the Jap dive bombers arrived over our forces; these were experienced pilots, not novices.

They were astounded by the Zero's superiority:

In the Coral Sea, they made all their approaches from the rear or high side and did relatively little damage because of our armor. It also is desired to call attention to the fact that there was an absence of the fancy stunting during pull outs or approaches for attacks. In this battle, the Japs dove in, made the attack and then immediately pulled out, taking advantage of their superior climb and maneuverability. In attacking fighters, the Zeros usually attacked from above rear at high speed and recovered by climbing vertically until they lost some speed and then pulled on through to complete a small loop of high wing over which placed them out of reach and in position for another attack. By reversing the turn sharply after each attack the leader may get a shot at the enemy while he is climbing away or head on into a scissor if the Jap turns to meet it.

In contrast, Allied fighters were designed with ruggedness and pilot protection in mind. The Japanese ace Saburō Sakai described how the resilience of early Grumman aircraft was a factor in preventing the Zero from attaining total domination:

I had full confidence in my ability to destroy the Grumman and decided to finish off the enemy fighter with only my 7.7 mm machine guns. I turned the 20mm cannon switch to the 'off' position, and closed in. For some strange reason, even after I had poured about five or six hundred rounds of ammunition directly into the Grumman, the airplane did not fall, but kept on flying! I thought this very odd—it had never happened before—and closed the distance between the two airplanes until I could almost reach out and touch the Grumman. To my surprise, the Grumman's rudder and tail were torn to shreds, looking like an old torn piece of rag. With his plane in such condition, no wonder the pilot was unable to continue fighting! A Zero which had taken that many bullets would have been a ball of fire by now.

When the powerfully armed Lockheed P-38 Lightning — possessing four "light barrel" AN/M2 .50 cal. Browning machine guns and one 20 mm autocannon — and the Grumman F6F Hellcat and Vought F4U Corsair, each using six of the AN/M2 heavy calibre Browning guns appeared in the Pacific theater, the A6M, with its low-powered engine and lighter armament, was hard-pressed to remain competitive. In combat with an F6F or F4U, the only positive thing that could be said of the Zero at this stage of the war was that in the hands of a skillful pilot it could maneuver as well as most of its opponents. Nonetheless, in competent hands the Zero could still be deadly.

Due to shortages of high-powered aviation engines and problems with planned successor models, the Zero remained in production until 1945, with over 11,000 of all variants produced.

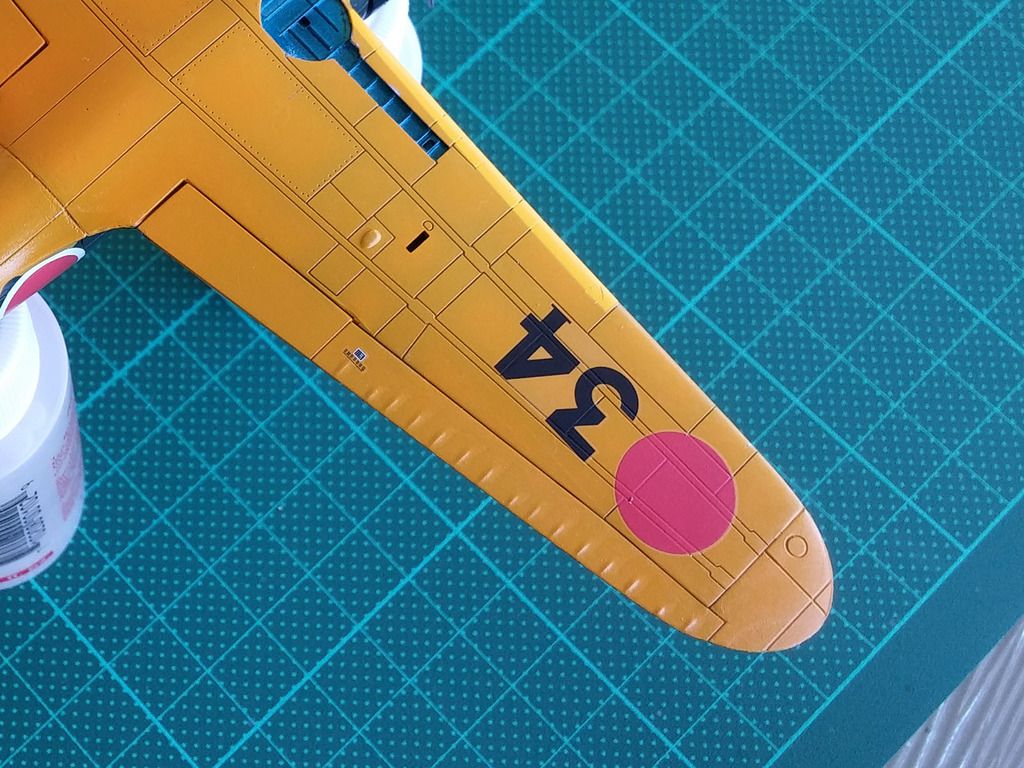

- captured_a6m5_in_flight_1944.jpg (345.43 KiB) Viewed 2307 times

I made this kit about 18 months ago when I first started the hobby and looking trough your build reminds me of just how good this kit is