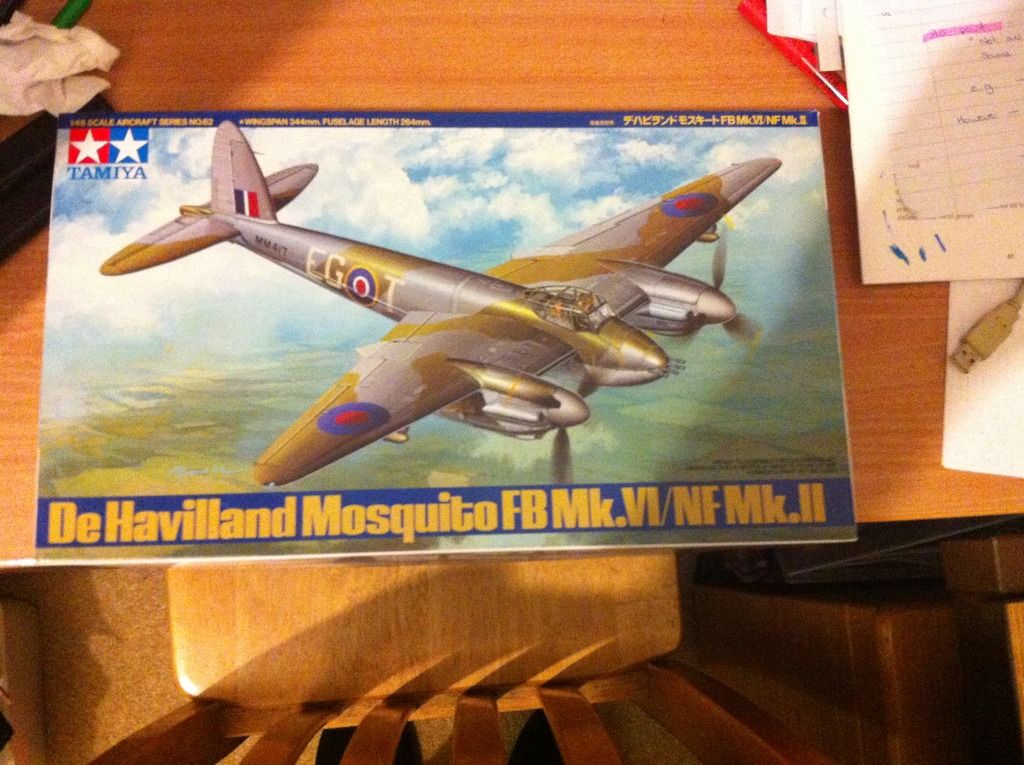

Hi Guys well she is here at last the wife and kids got me this for my birthday but have let me have it early so i cna get started on it.

Here is some history of this amazing aircraft (taken from the interweb)

The Wooden Wonder

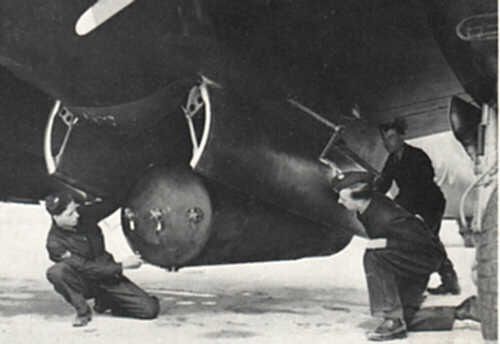

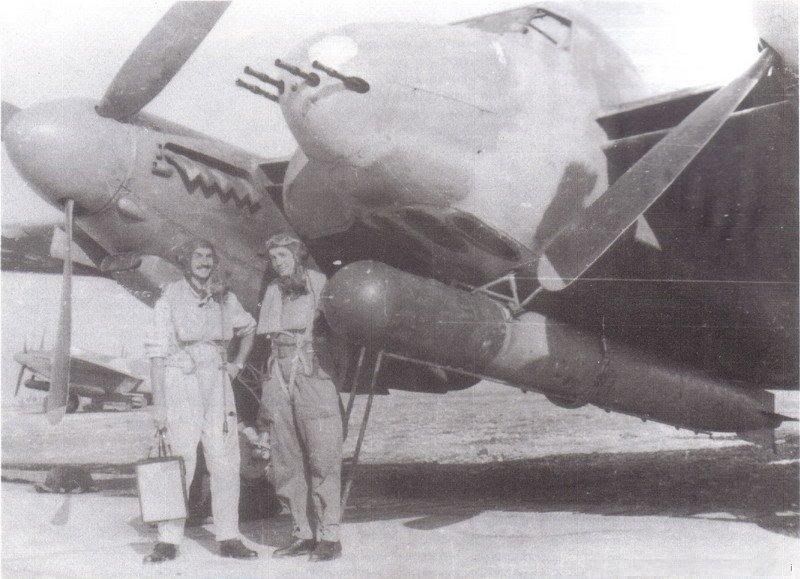

The de Havilland DH.98 Mosquito was a British multi-role combat aircraft with a two-man crew that served during and after the Second World War. It was one of few operational front-line aircraft of the era constructed almost entirely of wood and was nicknamed "The Wooden Wonder". The Mosquito was also known affectionately as the "Mossie" to its crews. Originally conceived as an unarmed fast bomber, the Mosquito was adapted to roles including low to medium-altitude daytime tactical bomber, high-altitude night bomber, pathfinder, day or night fighter, fighter-bomber, intruder, maritime strike aircraft, and fast photo-reconnaissance aircraft. It was also used by the British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) as a fast transport to carry small high-value cargoes to, and from, neutral countries, through enemy-controlled airspace. A single passenger could be carried in the aircraft's bomb bay, which was adapted for the purpose.

When the Mosquito began production in 1941, it was one of the fastest operational aircraft in the world. Entering widespread service in 1942, the Mosquito was a high-speed, high-altitude photo-reconnaissance aircraft, continuing in this role throughout the war. From mid-1942 to mid-1943 Mosquito bombers flew high-speed, medium or low-altitude missions against factories, railways and other pinpoint targets in Germany and German-occupied Europe. From late 1943, Mosquito bombers were formed into the Light Night Strike Force and used as pathfinders for RAF Bomber Command's heavy-bomber raids. They were also used as "nuisance" bombers, often dropping Blockbuster bombs - 4,000 lb (1,812 kg) "cookies" - in high-altitude, high-speed raids that German night fighters were almost powerless to intercept.

As a night fighter, from mid-1942, the Mosquito intercepted Luftwaffe raids on the United Kingdom, notably defeating Operation Steinbock in 1944. Starting in July 1942, Mosquito night-fighter units raided Luftwaffe airfields. As part of 100 Group, it was a night fighter and intruder supporting RAF Bomber Command's heavy bombers and reduced bomber losses during 1944 and 1945. As a fighter-bomber in the Second Tactical Air Force, the Mosquito took part in "special raids", such as the attack on Amiens Prison in early 1944, and in precision attacks against Gestapo or German intelligence and security forces. Second Tactical Air Force Mosquito supported the British Army during the 1944 Normandy Campaign. From 1943 Mosquito with RAF Coastal Command strike squadrons attacked Kriegsmarine U-boats (particularly in the 1943 Bay of Biscay, where significant numbers were sunk or damaged) and intercepting transport ship concentrations.

The Mosquito flew with the Royal Air Force (RAF) and other air forces in the European, Mediterranean and Italian theatres. The Mosquito was also operated by the RAF in the South East Asian theatre, and by the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) based in the Halmaheras and Borneo during the Pacific War.

Development

By the early-mid-1930s, de Havilland had a reputation for innovative high-speed aircraft with the DH.88 Comet racer. The later DH.91 Albatross airliner pioneered the composite wood construction that the Mosquito used. The 22-passenger Albatross could cruise at 210 miles per hour (340 km/h) at 11,000 feet (3,400 m), better than the 100 miles per hour (160 km/h) Handley Page H.P.42 and other biplanes it was replacing. The wooden monocoque construction not only saved weight and compensated for the low power of the de Havilland Gipsy Twelve engines used by this aircraft, but simplified production and reduced construction time.

Air Ministry bomber requirements and concepts

On 8 September 1936, the British Air Ministry issued Specification P.13/36 which called for a twin-engined medium bomber capable of carrying a bomb load of 3,000 pounds (1,400 kg) for 3,000 miles (4,800 km) with a maximum speed of 275 miles per hour (443 km/h) at 15,000 feet (4,600 m); a maximum bomb load of 8,000 pounds (3,600 kg) which could be carried over shorter ranges was also specified. Aviation firms entered heavy designs with new high-powered engines and multiple defensive turrets, leading to the production of the Avro Manchester and Handley Page Halifax.

In May 1937, as a comparison to P.13/36, George Volkert, the chief designer of Handley Page, put forward the concept of a fast unarmed bomber. In 20 pages, Volkert planned an aerodynamically clean medium bomber to carry 3,000 pounds (1,400 kg) of bombs at a cruising speed of 300 miles per hour (480 km/h). There was support in the RAF and Air Ministry; Captain R N Liptrot, Research Director Aircraft 3 (RDA3), appraised Volkert's design, calculating that its top speed would exceed the new Supermarine Spitfire. There were, however, counter-arguments that, although such a design had merit, it would not necessarily be faster than enemy fighters for long. The ministry was also considering using non-strategic materials for aircraft production, which, in 1938, had led to specification B.9/38 and the Armstrong Whitworth Albemarle medium bomber, largely constructed from spruce and plywood attached to a steel-tube frame. The idea of a small, fast bomber gained support at a much earlier stage than sometimes acknowledged though it was likely that the Air Ministry envisaged it using light alloy components.

Inception of the de Havilland fast bomber

Geoffrey de Havilland also believed a bomber with an aerodynamic design, with minimal skin area, was better than the P.13/36 specification. He thought that adapting the Albatross to meet the RAF's requirements could save time. In April 1938, performance estimates were produced for a twin Rolls-Royce Merlin-powered DH.91, with the Bristol Hercules (radial engine) and Napier Sabre (H-engine) as alternatives. On 7 July 1938, Geoffrey de Havilland wrote to Air Marshal Wilfrid Freeman, the Air Council's member for Research and Development, discussing the specification and arguing that in war there would be shortages of duralumin and steel but should be plenty of wood. Although inferior torsionally, the strength to weight ratio of wood was as good as duralumin or steel, and a different approach to a high-speed bomber was possible.

A follow-up letter to Freeman on 27 July said that the P.13/36 specification could not be met by a twin Merlin-powered aircraft and either the top speed or load capacity would be compromised, depending on which was paramount. For example, a larger, slower, turret armed aircraft would have a range of 1,500 miles (2,400 km) carrying a 4,000-pound (1,800 kg) bomb load, with a maximum of 260 miles per hour (420 km/h) at 19,000 feet (5,800 m), and a cruising speed of 230 miles per hour (370 km/h) at 18,000 feet (5,500 m). De Havilland believed that too much of a compromise, and that getting rid of surplus equipment would lead to a better design. On 4 October 1938, de Havilland projected the performance of another design based on the Albatross, powered by two Merlin Xs, with a three-man crew and six or eight forward-firing guns, plus one or two manually operated guns and a tail turret. Based on a total loaded weight of 19,000 lb (8,600 kg) it would have a top speed of 300 mph (480 km/h) and cruising speed of 268 mph (431 km/h) at 22,500 ft (6,900 m).

Still believing this could be improved, and after examining more concepts based on the Albatross and the new all-metal DH.95 Flamingo, de Havilland settled on designing a new aircraft that would be aerodynamically clean, wooden and powered by the Merlin, which offered substantial future development. The new design would be faster than foreseeable enemy fighter aircraft, and could dispense with a defensive armament, which would slow it and make interception or losses to anti-aircraft guns more likely. Instead, high speed and good manoeuvrability would make it easier to evade fighters and ground fire. The lack of turrets simplified production and reduced production time, with a delivery rate far in advance of competing designs. Without armament, the crew could be reduced to a pilot and navigator. Contemporary RAF design philosophy required well-armed heavy bombers more akin to the German schnellbomber. At a meeting in early October 1938 with Geoffrey de Havilland and Charles Walker (de Havilland's chief engineer), the Air Ministry showed little interest, and instead asked de Havilland to build wings for other bombers as a sub-contractor.

By September 1939 de Havilland had produced preliminary estimates for single- and twin-engined variations of light-bomber designs using different engines, speculating on the effects of defensive armament on their designs. One design, completed on 6 September, was for an aircraft powered by a single 2,000 hp (1,500 kW) Napier Sabre, with a wingspan of 47-foot (14 m) and capable of carrying a 1,000 pounds (450 kg) bomb load 1,500 miles (2,400 km). On 20 September, in another letter to Wilfred Freeman, de Havilland wrote "...we believe that we could produce a twin-engine bomber which would have a performance so outstanding that little defensive equipment would be needed." By 4 October work had progressed to a twin-engine light bomber with a wingspan of 51 ft 3 in (15.62 m), and powered by Merlin or Griffon engines, the Merlin favoured due to availability. On 7 October 1939, a month into the war, the nucleus of a design team under Eric Bishop moved to the security and secrecy of Salisbury Hall to work on what was later known as the DH.98. For more versatility, Bishop made provision for four 20 mm cannon in the forward half of the bomb bay, under the cockpit, firing via blast tubes and troughs under the fuselage.

The DH.98 was too radical for the Ministry, which wanted a heavily armed, multi-role aircraft, combining medium bomber, reconnaissance and general purpose roles, as well as capable of carrying torpedoes. With outbreak of war, the Ministry became more receptive, but still skeptical about an unarmed bomber. It thought the Germans would produce fighters faster than expected. It suggested two forward and two rear-firing machine guns for defense. The Ministry also opposed a two-man bomber, wanting at least a third crewman to reduce the work of the others on long flights. The Air Council added further requirements, such as remotely controlled guns, a top speed of 275 mph (443 km/h) at 15,000 ft (4,600 m) on two-thirds engine power, and a range of 3,000 mi (4,800 km) with a 4,000 lb (1,800 kg) bomb load. To appease the Ministry, de Havilland built mock-ups with a gun turret just aft of the cockpit but, apart from this compromise, de Havilland made no changes.

On 12 November, at a meeting considering fast bomber ideas put forward by de Havilland, Blackburn, and Bristol, Air Marshal Freeman directed de Havilland to produce a fast aircraft, powered initially by Merlin engines, with options of using progressively more powerful engines, including the Rolls-Royce Griffon and the Napier Sabre. Although estimates were presented for a slightly larger Griffon-powered aircraft, armed with a four-gun tail turret, Freeman got the requirement for defensive weapons dropped, and a draft requirement was raised calling for a high-speed light reconnaissance bomber capable of 400 mph (640 km/h) at 18,000 ft (5,500 m).

On 12 December, the Vice-Chief of the Air Staff, Director General of Research and Development, Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief (AOC-in-C) of RAF Bomber Command met to finalize the design and decide how to fit it in the RAF's aims. The AOC-in-C would not accept an unarmed bomber, but insisted on its suitability for reconnaissance missions with F8 or F24 cameras. After company representatives, the Ministry and the RAF's operational commands examined a full-scale mock-up at Hatfield on 29 December 1939, the project received backing. This was confirmed on 1 January 1940, when Air Marshal Freeman chaired a meeting with Geoffrey de Havilland, John Buchanan, (Deputy of Aircraft Production) and John Connolly (Buchanan's chief of staff). de Havilland claimed the DH.98 was the "fastest bomber in the world...it must be useful". Freeman supported it for RAF service, ordering a single prototype for an unarmed bomber to specification B.1/40/dh, which called for a light bomber/reconnaissance aircraft powered by two 1,280 hp (950 kW) Rolls-Royce RM3SM (an early designation for the Merlin 21) with ducted radiators, capable of carrying a 1,000 pounds (450 kg) bomb load.[18][24] The aircraft was to have a speed of 397 miles per hour (639 km/h) at 23,700 feet (7,200 m) and a cruising speed of 327 miles per hour (526 km/h) at 26,600 feet (8,100 m) with a range of 1,480 miles (2,380 km) at 24,900 feet (7,600 m) on full tanks. Maximum service ceiling was to be 32,100 feet (9,800 m).

On 1 March 1940, Air Marshal Roderic Hill issued a contract under Specification B.1/40, for 50 bomber-reconnaissance variants of the DH.98: this contract included the prototype, which was given the factory serial E0234. In May 1940, specification F.21/40 was issued, calling for a long-range fighter armed with four 20 mm cannon and four .303 machine guns in the nose, after which de Havilland were authorized to build a prototype of a fighter version of the DH.98. It was decided after debate that this prototype, given the military serial number W4052, would carry Airborne Interception (AI) Mk.IV equipment as a day and night fighter. By June 1940, the DH.98 had been named "Mosquito". Having the fighter variant kept the Mosquito project alive because there was still criticism within the government and Air Ministry of the usefulness of an unarmed bomber, even after the prototype had shown its capabilities.

Project Mosquito

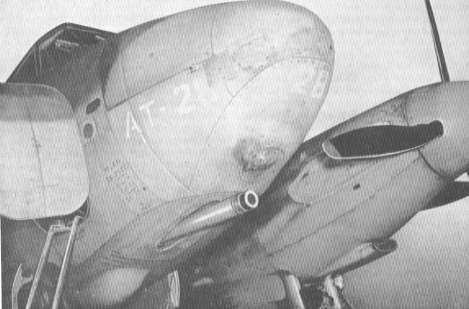

Once design of the DH.98 had started, de Havilland built mock-ups, the most detailed at Salisbury Hall, in the hangar where E0234 was being built. Initially, this was designed with the crew enclosed in the fuselage behind a transparent nose (similar to the Bristol Blenheim or Heinkel He 111H), but this was quickly altered to a more solid nose with a more conventional canopy.

The construction of the prototype began in March 1940, but work was cancelled again after the Battle of Dunkirk, when Lord Beaverbrook, as Minister of Aircraft Production, decided there was no production capacity for aircraft like the DH.98, which was not expected to be in service until early 1941. Although Lord Beaverbrook told Air Vice-Marshal Freeman that work on the project should stop, he did not issue a specific instruction, and Freeman ignored the request. In June 1940, however, Lord Beaverbrook and the Air Staff ordered that production focus on five existing types, namely the Supermarine Spitfire, Hawker Hurricane, Vickers Wellington, Armstrong-Whitworth Whitley and the Bristol Blenheim. Work on the DH.98 prototype stopped; it seemed that the project would be shut down when the design team were denied the materials with which to build their prototype.

The Mosquito was only reinstated as a priority in July 1940, after de Havilland's General Manager L.C.L Murray, promised Lord Beaverbrook 50 Mosquitoes by December 1941, and this, only after Beaverbrook was satisfied that Mosquito production would not hinder de Havilland's primary work of producing Tiger Moth and Oxford trainers and repairing Hurricanes as well as the licence manufacture of Merlin engines. In promising Beaverbrook 50 Mosquitoes by the end of 1941, de Havilland was taking a gamble, because it was unlikely that 50 Mosquito's could be built in such a limited time; as it transpired only 20 Mosquito's were built in 1941, but the other 30 were delivered by mid-March 1942. During the Battle of Britain, interruptions to production due to air raid warnings caused nearly a third of de Havilland's factory time to be lost. Nevertheless, work on the prototype went quickly, such that E0234 was rolled out on 19 November 1940.

In the aftermath of the Battle of Britain, the original order was changed to 20 bomber variants and 30 fighters. It was still uncertain whether the fighter version should have dual or single controls, or should carry a turret, so three prototypes were eventually built: W4052, W4053 and W4073. The latter, both turret armed, were later disarmed, to become the prototypes for the T.III trainer. This caused some delays as half-built wing components had to be strengthened for the expected higher combat load requirements. The nose sections also had to be altered, omitting the clear perspex bomb-aimer's position, to solid noses designed to house four .303 machine guns and their ammunition.

Prototypes and test flights

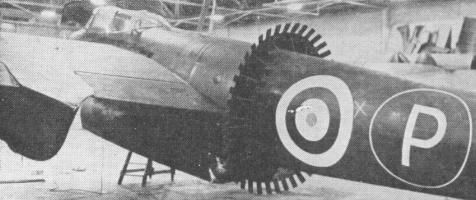

On 3 November 1940, the aircraft, still coded E0234, was transported by road to Hatfield, and placed in a small blast-proof assembly building, where successful engine runs were made on 19 November. Two Merlin 21 two-speed single-stage supercharged engines were installed driving three-bladed de Havilland Hydromatic constant-speed, controllable-pitch propellers. E0234 had a wingspan of 52 ft 2 in (15.90 m) and was the only Mosquito to be built with Handley Page slats on the outer leading edges of the wings. Test flights showed that these were not needed and they were disconnected and faired over with doped fabric (these slats can still be seen on W4050). On 24 November 1940, taxiing trials were carried out by Geoffrey de Havilland, Jr., who was the company's chief test pilot and responsible for maiden flights. The tests were successful and the prototype was subsequently readied for flight testing, making its first flight piloted by Geoffrey de Havilland, on 25 November. The flight was made 11 months after the start of detailed design work, a remarkable achievement considering the conditions of the time.

For this maiden flight, E0234, weighing 14,150 pounds (6,420 kg), took off from a 450-foot (140 m) field beside the shed it was built in. John E. Walker, Chief Engine Installation designer, accompanied de Havilland. The takeoff was "straight forward and easy" and the undercarriage was not retracted until a considerable height was attained. The aircraft reached 220 mph (350 km/h), with the only problem being the undercarriage doors - which were operated by bungee cords attached to the main undercarriage legs - that remained open by some 12 inches (300 mm) at that speed. This problem persisted for some time. The left wing of E0234 also had a tendency to drag to port slightly, so a rigging adjustment was carried out before further flights.

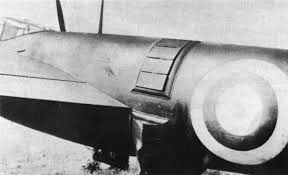

On 5 December 1940, the prototype experienced tail buffeting at speeds between 240 miles per hour (390 km/h) and 255 miles per hour (410 km/h). The pilot noticed this most in the control column, with handling becoming more difficult. During testing on 10 December, wool tufts were attached to suspect areas to investigate the direction of airflow. The conclusion was that the airflow separating from rear section of the inner engine nacelles was disturbed, leading to a localised stall and the disturbed airflow was striking the tailplane, causing buffeting. In an attempt to smooth the air flow and deflect it from forcefully striking the tailplane, non-retractable slots fitted to the inner engine nacelles and to the leading edge of the tailplane were experimented with. These slots, and wing root fairings fitted to the forward fuselage and leading edge of the radiator intakes, stopped some of the vibration experienced but did not cure the tailplane buffeting. In February 1941, buffeting was eliminated by incorporating triangular fillets on the trailing edge of the wings and lengthening the nacelles, the trailing edge of which curved up to fair into the fillet some 10 in (250 mm) behind the wing's trailing edge: this meant the flaps had to be divided into inboard and outboard sections.

By January 1941, the prototype was carrying the military serial number W4050. With the buffeting problems largely resolved, John Cunningham flew W4050 on 9 February 1941. He was greatly impressed by the "lightness of the controls and generally pleasant handling characteristics". Cunningham concluded that when the type was fitted with AI equipment, it would be a perfect replacement for the Bristol Beaufighter.

During its trials on 16 January 1941, W4050 outpaced a Spitfire at 6,000 ft (1,800 m). The original estimates were that as the Mosquito prototype had twice the surface area and over twice the weight of the Spitfire Mk II, but also with twice its power, the Mosquito would end up being 20 miles per hour (32 km/h) faster. Over the next few months, W4050 surpassed this estimate, easily beating the Spitfire Mk II in testing at RAF Boscombe Down in February 1941, reaching a top speed of 392 miles per hour (631 km/h) at 22,000 feet (6,700 m) altitude, compared to a top speed of 360 miles per hour (580 km/h) at 19,500 feet (5,900 m) for the Spitfire. On 19 February, official trials began at the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment (A&AEE) based at Boscombe Down, although de Havilland's representative was surprised by a delay in starting the tests. On 24 February, as W4050 taxied across the rough airfield, the tailwheel jammed leading to the fuselage fracturing: this was replaced by the fuselage of the Photo-Reconnaissance prototype W4051 in early March. In spite of this setback, the Initial Handling Report 767 issued by the A&AEE stated "The aeroplane is pleasant to fly ... Aileron control light and effective ..." The maximum speed reached was 388 mph (624 km/h) at 22,000 ft (6,700 m), with an estimated maximum ceiling of 33,900 ft (10,300 m) and a maximum rate of climb of 2,880 ft/min (880 m/min) at 11,400 ft (3,500 m).

W4050 continued to be used for various test programs, essentially as the experimental "workhorse" for the Mosquito family. In late October 1941, it returned to the factory to be fitted with Merlin 61s, the first production Merlins fitted with a two-speed, two-stage supercharger. The first flight with the new engines was on 20 June 1942. W4050 recorded a maximum speed of 428 mph (689 km/h) at 28,500 ft (8,700 m) (fitted with straight-through air intakes with snowguards, engines in F.S. gear) and 437 mph (703 km/h) at 29,200 ft (8,900 m) without snowguards. In October 1942, in connection with development work on the NF Mk XV, W4050 was fitted with extended wingtips increasing the span to 59 ft 2 in (18.03 m), first flying in this configuration on 8 December. Finally, fitted with high-altitude rated two-stage, two-speed Merlin 77s, it reached 439 miles per hour (707 km/h) in December 1943. Soon after these flights,W4050 was grounded and was scheduled to be scrapped, but instead served as an instructional airframe at Hatfield. In September 1958, W4050 was returned to the Salisbury Hall hangar in which it had been built, restored to its original configuration, and became one of the primary exhibits of the de Havilland Aircraft Heritage Centre.

W4051, which was designed from the outset to be the prototype for the photo-reconnaissance versions of the Mosquito, was slated to make its first flight in early 1941. However, the fuselage fracture in W4050 meant that W4051's fuselage was used as a replacement; W4051 was then rebuilt using a production standard fuselage and first flew on 10 June 1941. This prototype continued to use the short engine nacelles, single-piece trailing edge flaps and the 19 ft 5.5 in (5.931 m) "No. 1" tailplane used by W4050, but had production standard 54 ft 2 in (16.51 m) wings and, thus configured, became the only Mosquito prototype to fly operationally.

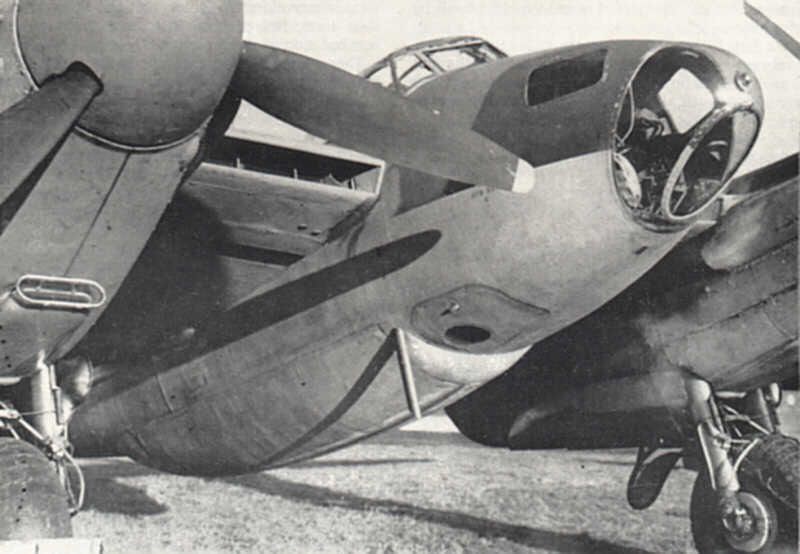

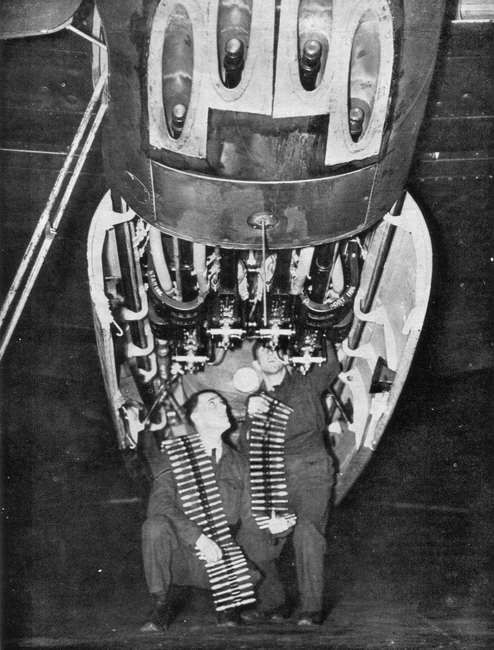

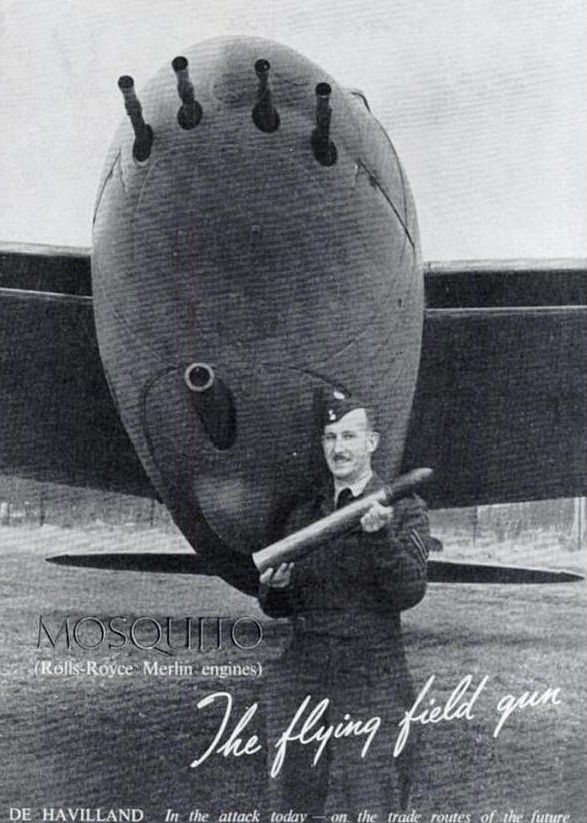

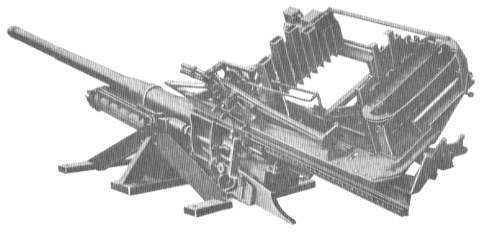

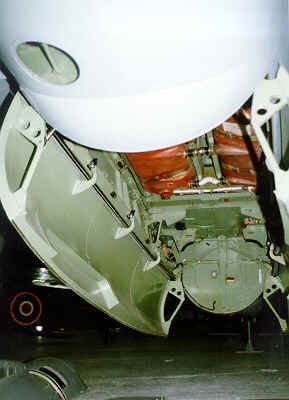

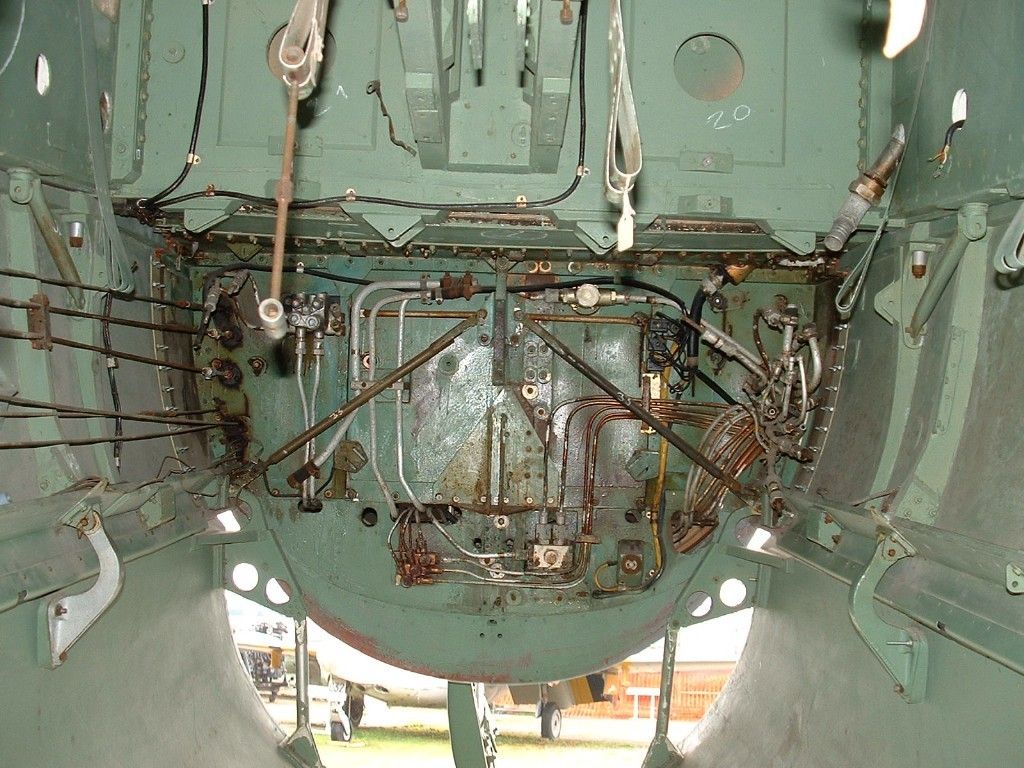

Construction of the fighter prototype, W4052 was also carried out at the secret Salisbury Hall facility. The new prototype differed from its bomber brethren in a number of ways. It was powered by 1,460 hp (1,090 kW) Merlin 21s and had an altered canopy structure with a flat bullet-proof windscreen. Four 20 mm (.79 in) Hispano Mk II cannon were housed in a compartment under the cockpit floor, with the breeches projecting into the bomb bay. The bomb bay doors were replaced by manually operated bay doors which incorporated cartridge ejector chutes. The solid nose mounted four .303 in (7.7 mm) Browning machine guns and their ammunition boxes which were accessed by a single large, sideways hinged panel. In accordance with its role as a day/night fighter prototype W4052 was equipped with AI Mk.IV equipment, complete with an "arrowhead"-shaped transmission aerial mounted between the central Brownings, and receiving aerials through each outer wingtip, and it was painted in overall black RDM2a "Special Night" finish. It was also the first prototype constructed with the extended engine nacelles.

W4052 was later tested with other modifications including bomb racks, drop tanks, barrage balloon cable cutters in the leading edge of the wings, Hamilton airscrews and braking propellers, as well as drooping aileron systems which enabled steep approaches, and a larger rudder tab. The prototype continued to serve as a test machine until it was scrapped on 28 January 1946. W4055 flew the first operational Mosquito flight on 17 September 1941.

During flight testing, the Mosquito prototypes were modified to test a number of experimental configurations. W4050 was fitted with a turret behind the cockpit for drag tests, after which the idea was abandoned in July 1941. W4052 had the first version of the Youngman Frill airbrake fitted to the fighter prototype. The frill was opened by bellows and venturi effect to provide rapid deceleration during interceptions and was tested between January - August 1942, but was also abandoned when it was discovered that lowering the undercarriage had the same effect with less buffeting.

Production plans and American interest

The Air Ministry had authorised mass production plans to be drawn up on 21 June 1941, by which time the Mosquito had become one of the world's fastest operational aircraft. The Air Ministry ordered 19 photo-reconnaissance (PR) models and 176 fighters. A further 50 were unspecified; in July 1941, the Air Ministry confirmed these would be unarmed fast bombers. By the end of January 1942, contracts had been awarded for 1,378 Mosquitos of all variants, including 20 T.III trainers and 334 FB.VI bombers. Another 400 were to be built by de Havilland Canada.

On 20 April 1941, W4050 was demonstrated to Lord Beaverbrook, the Minister of Aircraft Production. The Mosquito made a series of flights, including one rolling climb on one engine. Also present were US General Henry H. Arnold and his aide Major Elwood Quesada, who wrote "I ... recall the first time I saw the Mosquito as being impressed by its performance, which we were aware of. We were impressed by the appearance of the airplane that looks fast usually is fast, and the Mosquito was, by the standards of the time, an extremely well streamlined airplane, and it was highly regarded, highly respected."

The trials set up future production plans between Britain, Australia and Canada. The Americans did not pursue their interest. It was thought the Lockheed P-38 Lightning could handle the same duties just as easily. Arnold felt the design was being overlooked, and urged the strategic personalities in the United States Army Air Forces to learn from the design if they chose not to adopt it. Several days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the USAAF then requested one airframe to evaluate on 12 December 1941, signifying that the USAAF realised that they had entered the war without a fast dual-purpose reconnaissance aircraft.

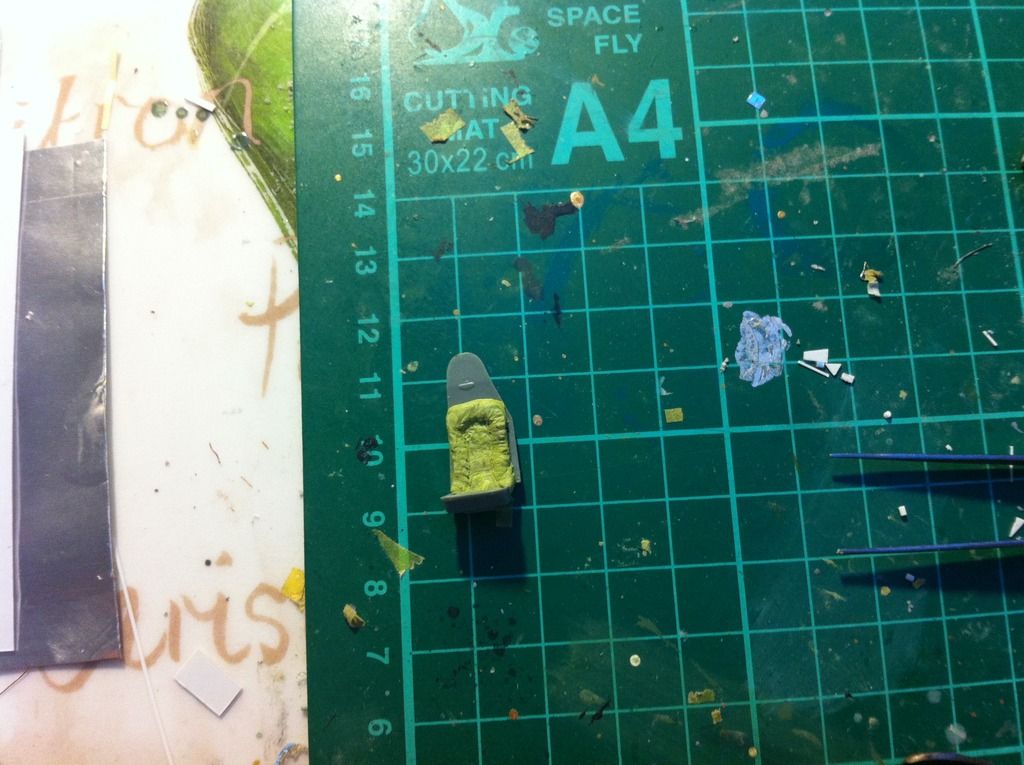

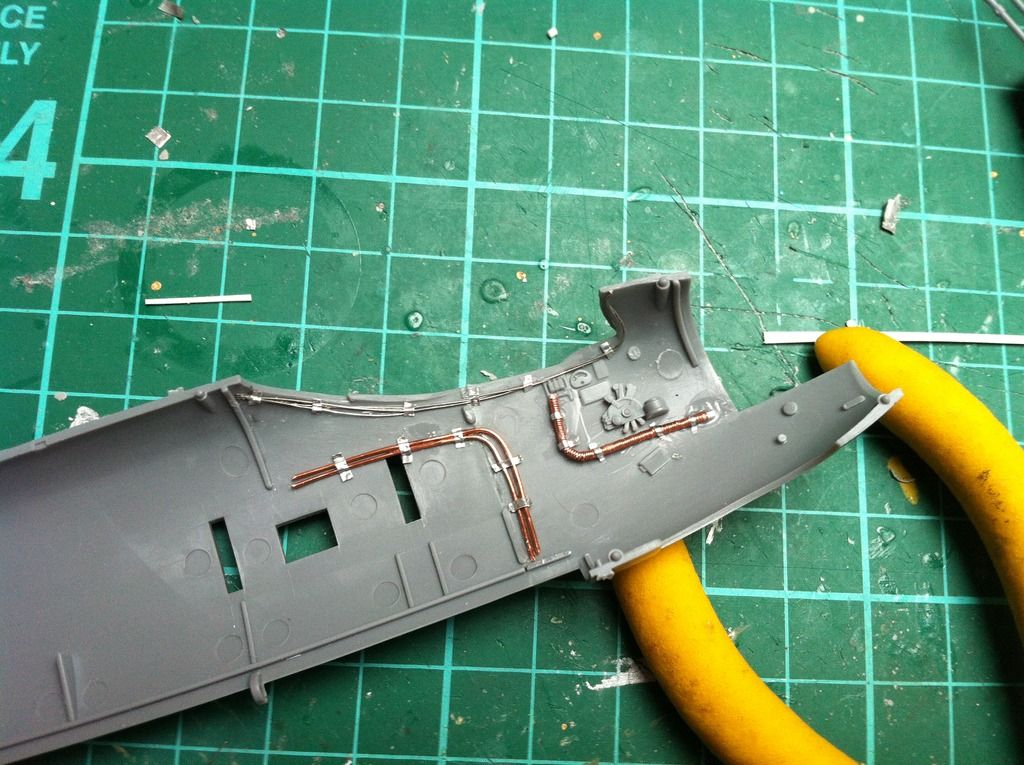

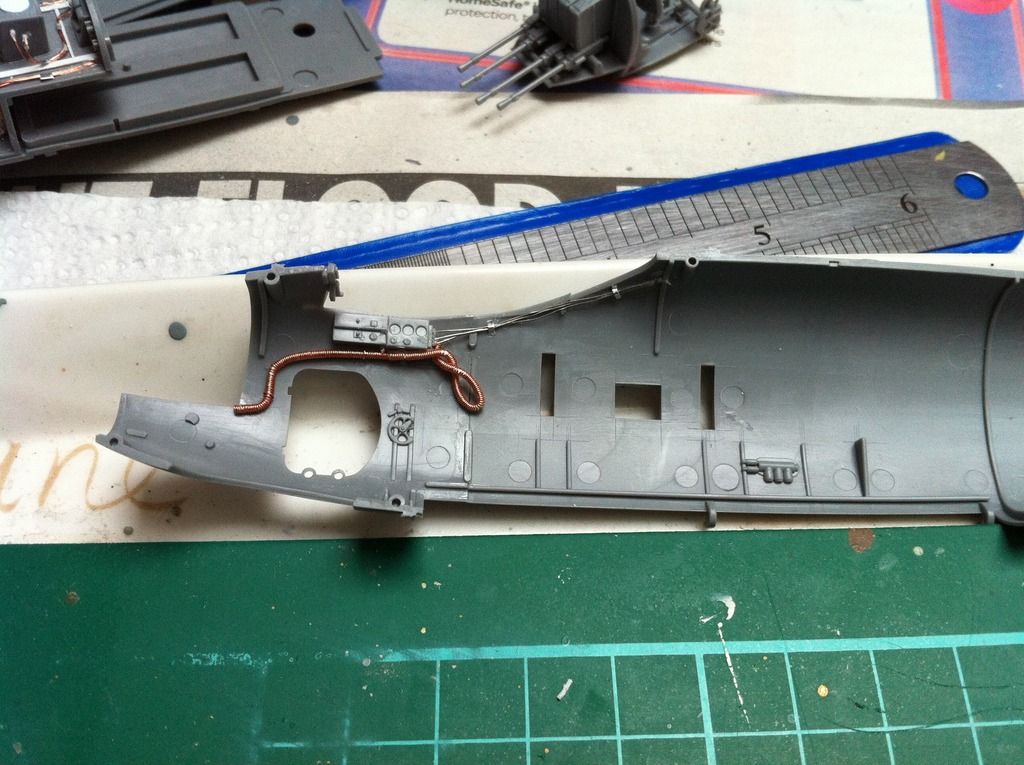

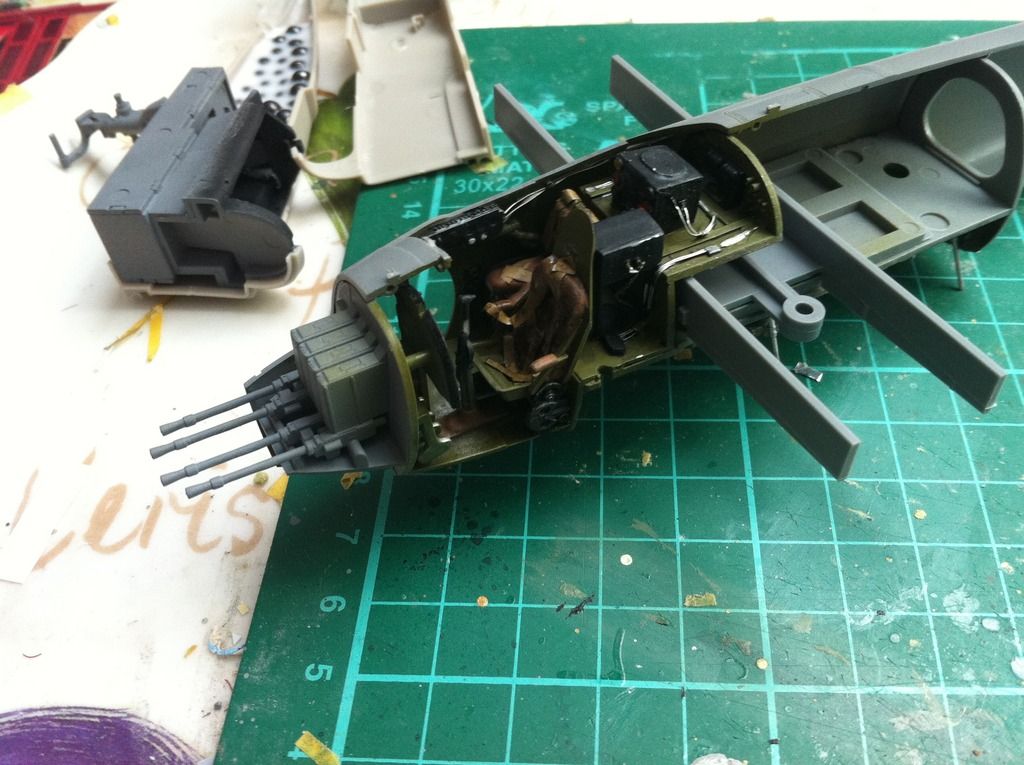

Im hoping to get started on the build soon